By: Megan Brosnan

By: Megan Brosnan

After decades of dedicated research, Nike introduced its groundbreaking Flyknit technology in 2012, marking a transformative moment in the evolution of contemporary running shoe design.[1] The impact of this innovation is evident in the extensive portfolio of over three hundred patents that Nike now holds for its Flyknit technology.[2] By leveraging “strong yet lightweight strands of yarn,” Flyknit provides athletes with a harmonious blend of stability, airflow, and comfort.[3] The essence of this technology lies in Nike’s strategic approach – utilizing fewer materials and weaving shoes with tighter knits, all while incorporating targeted areas for enhanced foot support.[4] Beyond performance benefits, Nike is committed to sustainability, aiming to reduce environmental impact. A noteworthy accomplishment, as highlighted by a 2016 study from New York University’s Center for Sustainable Business, reveals that Nike’s Flyknit technology alone has contributed to a reduction of 3.5 million pounds of waste by repurposing various forms of leftover scraps.[5]

In the past few years, Nike has sued Adidas, Lululemon, and Puma for infringing on its Flyknit technology patents.[6] Adidas and Puma settled; however, Lululemon and Nike are set to meet in court in December 2023.[7] Nike has also recently lodged separate complaints against New Balance and Sketchers, citing similar patent infringement concerns.[8] If the matter proceeds to trial, the court will first determine the validity of Nike’s Flyknit technology patents. If deemed valid, the court will then assess whether New Balance and other companies have infringed on these patents.[9]

On January 30, 2023, Nike sued Lululemon for patent infringement.[10] Nike’s complaint referred to three of its patents. The first patent, 8,266,749, describes “a method of manufacturing an article of footwear with a textile element, where the textile element is simultaneously knitted with a surrounding textile structure, and the textile element has a knitted texture that differs from the knitted texture in the surrounding textile structure.”[11] Patent No. 9,375,046 and Patent No. 9,730,484 refer to elements of Flyknit that relate to the movement of an athlete’s foot on the sides and top of the shoe.[12] Lululemon disagreed with Nike’s allegations.[13] In a counterclaim, Lululemon posited that Nike failed to state a claim for patent infringement and that the three patents are invalid under the doctrine of obviousness and prior art.[14]

A patent undergoes extensive examination before receiving a patent from the United States Patent and Trademark Office (“USPTO”). During this evaluation, an examiner assesses the proposed invention’s novelty and non-obviousness by comparing it to existing “prior art.”[15] The USPTO only approves non-obvious, also known as novel, patents.[16]When Nike submitted its Flyknit patent application to the USPTO, the examiner rejected claims 1-21.[17] Claims 1-21failed under the theory of obviousness-type double patenting.[18] More specifically, claims 1-8, 11-18, and 21 did not meet the USPTO’s criteria, as another shoe company, Nishida, had employed a similar knitting method.[19] Following extensive communication with the USPTO, Nike successfully secured a comprehensive list of patents for Flyknit technology, demonstrating its non-obvious nature.[20] However, similar to Lululemon, New Balance may raise challenges to the validity of these patents.

Shoe companies spend billions of dollars on research and development; however, all footwear maintains the same basic outline.[21] Nearly every major shoe company assembles shoes with knitted uppers, which begs the question of the strength of Nike’s Flyknit patents.[22] If Nike can prove that their patents were non-obvious at the time the company submitted the patent application, then Nike’s patents are valid. However, if New Balance and Lululemon provide evidence against the novelty of Nike’s invention, then Nike’s patent is invalid under the doctrine of obviousness.

The initial inquiry a court faces is whether a person with average skills in the relevant field could consider the claimed invention as obvious.[23] Adidas’s Primeknit complicates the argument against the “obviousness” of Nike’s Flyknit. Approximately a year after Nike introduced its Flyknit patents, Adidas unveiled a comparable shoe. Adidas contended that “the timing was just an example of the same idea bubbling to the surface in different parts of the market because both manufacturers were searching for innovative and more sustainable techniques.”[24] Around 2013, as shoe companies encountered criticism from both consumers and journalists, there was a collective industry effort to explore novel methods for crafting sustainable footwear and minimizing reliance on child labor.[25] New Balance and Lululemon may challenge the validity of Nike’s patents by emphasizing that the majority of shoe companies embarked on the quest for more sustainable designs in the early 2000s.[26] They can argue that the notion of utilizing recycled materials with knit technology was likely considered by shoe designers numerous times. By doing so, these companies can counter the non-obviousness claim associated with Nike’s Flyknit patents.

Whether the courts ultimately categorize Nike as a patent predator or protector, these lawsuits vividly demonstrate Nike’s substantial market power and influence. With a portfolio exceeding three hundred patents, Nike effectively restricts competitors from innovating upon an arguably “obvious” technique aimed at reducing carbon emissions.Currently, global shoe manufacturing generates massive waste.[27] Rather than suing competitors, Nike should allow other companies to utilize its eco-friendly Flyknit technology to support “Move to Zero” campaign.[28] Failing to relax its patent enforcement could expose Nike to legitimate challenges from New Balance and Lululemon regarding the validity of its patents, a matter that courts are likely to address in the near future.

Exhibits

Exhibit 1: Visualizing Nike’s Flyknit Technology

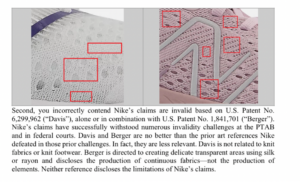

Exhibit 2: Showing Nike’s Comparison Between Its Shoe and New Balance’s Shoe

[1] Carley Fink, Nike:Sustainability and Innovation through Flyknit Technology, NYU Center for Sustainable Business, Aug. 2016 (demonstrating that Nike makes its shoes with one thread rather than adding pieces to the shoe individually. Nearly every major running shoe brand now creates shoes similarly).

[2] What is Flyknit Technology?, JD Style (last viewed Nov. 12, 2023), https://blog.jdsports.com/what-is-flyknit-technology/ (explaining that Flyknit reduces “waste by around 60%”).

[3] See id.; see also Nike Flyknit, Nike (last viewed Nov. 8, 2023), https://www.nike.com/flyknit.

[4] See id.

[5] Mary Roeloffs, Nike Claims New Balance and Sketchers Stole Technology for Sustainable Shoes in New Lawsuit, Forbes (Nov. 7, 2023), https://www.forbes.com/sites/maryroeloffs/2023/11/07/nike-claims-new-balance-and-skechers-stole-technology-for-sustainable-shoes-in-new-lawsuit/?sh=527a1ec31f2f; see also Lynn Paine, Governance and Sustainability at Nike (A), Harvard Business School Case 313-146, June 2013 (Revised April 2023) (indicating Nike’s commitment to sustainability with its development to the “Sustainable Business and Innovation Team”).

[6] Khristopher Brooks, Nike sues New Balance and Skechers over patent infringement, CBS News (Nov. 7, 2023), https://www.cbsnews.com/news/nike-new-balance-skechers-lawsuit-flyknit/.

[7] Nike, Inc. v. Lululemon U.S. Inc., No. 23CV771, 2023 U.S. Dist. LEXIS 163564 (S.D.N.Y. Jan. 30, 2023) (order regarding electronic discovery).

[8] Blake Brittain, Nike Sues New Balance, Skechers for patent infringement over sneaker technology, Reuters (Nov. 6, 2023), https://www.reuters.com/legal/litigation/nike-sues-new-balance-skechers-patent-infringement-over-sneaker-technology-2023-11-06/ (stating that New Balance “fully respects competitors’ intellectual property rights, but Nike does not own the exclusive right to design and produce footwear by traditional manufacturing methods that have been used in the industry for decades”).

[9]Adidas Primeknit Shoes, Adidas (last viewed Nov. 12, 2023), https://www.adidas.com/us/primeknit-shoes (comparing against Nike’s Flyknit technology).

[10] Nike is Suing Lululemon over Patent infringement, Again, Forbes (Feb. 6, 2023), https://www.forbes.com/sites/qai/2023/02/06/nike-is-suing-lululemon-over-patent-infringementagain-heres-what-investors-need-to-know-about-the-war-between-these-athletic-apparel-giants/?sh=efbaff555102.

[11] Complaint at 4, Nike, Inc. v. Lululemon U.S. Inc., No. 23CV771, 2023 U.S. Dist. LEXIS 163564 (S.D.N.Y. Jan. 30, 2023) (referring to Exhibit 1 for an example).

[12] See id. at 6-8.

[13] Answer, Nike, Inc. v. Lululemon U.S. Inc., No. 23CV771, 2023 U.S. Dist. LEXIS 163564 (S.D.N.Y. Mar. 24, 2023).

[14] 35 U.S.C. § 101, 102, 103, 112.

[15] Prior Art, Cornell Law School (last viewed Nov. 12, 2023), https://www.law.cornell.edu/wex/prior_art (defining “prior art” as “all information that is publicly available before someone claims to invent something”).

[16] 35 U.S.C. §102; 35 U.S.C. §103.

[17] Claims, U.S. Patent App. No. 13/236,742 (Sept. 20, 2011) (providing a list of Nike’s patent claims. Claim 1 – the Flyknit technology is a “method of manufacturing an article of footwear…[by] simultaneously knitting a textile element with a surrounding textile structure, the knitted textile element having at least one knitted texture that differs from a knitted texture in the surrounding knitted textile structure,” Claim 2 – a “plurality of textile elements,” Claims 3-4 – “knitting an outline of the knitted textile element…wherein the outline has the shape and proportion of the knitted textile element,” Claim 5 – “the knitted element has a substantially planar configuration upon removal from the surrounding knitted textile structure,” Claims 6-7 – “includes longitudinal edges….are joined together to define at least a portion of a void for receiving a foot,” Claim 8 – “varying at least one of the stitch type and yarn type,” Claim 9 – “a wide-tube circular knitting machine,” Claim 10 – “a jacquard double needle-bar raschel knitting machine,” Claim 11 – first stich different from second stitch; Claim 12 – “form a seam that extends along a lower region of an upper and securing the upper to a sole structure,” Claims 13-14 – explaining the method for manufacturing, Claim 15 – “knitted elements have substantially planar configurations upon removal from the surrounding knitted textile structure,” Claim 16 – “longitudinal edges when removed from surrounding knitted textile structure,” Claim 17 – ”longitudinal edges are joined together to define at least a portion of a void for receiving a foot,” Claim 18 – “securing longitudinal edges of the first knitted textile element to form a seam that extends along a lower region of an upper,” Claim 19-20 – combining the first and second textile knitted elements at the same time with a wide-tube circular knitting machine and a jacquard double needle-bar raschel knitting machine; Claim 21 – stiches create different textures; see also 35 U.S.C. § 102(b) (citing the “subject matter disclosed had, before such disclosure, been publicly disclosed by the inventor or a joint inventor or another who obtained the subject matter disclosed directly or indirectly from the inventor or a joint inventor”).

[18] Sarah Eddy et. al., Obviousness-type double patenting: terminal disclaimers and best IP practices, Norton Rose Fulbright, Sept. 2023 (explaining that the theory “the judicially-created obviousness-type double patenting doctrine is grounded in public policy and is intended to prevent a patentee from obtaining an unjust extension of the length of a patent’s right to exclude for an obvious modification, and to prevent potential harassment from multiple parties asserting non-commonly-owned patents for essentially the same invention.”); see also Office Action Summary, U.S. Patent App. No. 13/236,742 (Nov. 28, 2011); 25 U.S.C. § 103 (defining the “theory of obviousness “as an invention that a “person having ordinary skill in the art” would think as obvious before the “effective filing date”).

[19] Office Action Summary, U.S. Patent App. No. 13/236,742 (Nov. 28, 2011).

[20] U.S. Patent No. 8, 266,749 (issued Sept. 18, 2012) (referencing the full document here – chrome-extension://nlaealbpbmpioeidemdfedkfmglobidl/https://image-ppubs.uspto.gov/dirsearch-public/print/downloadPdf/8266749).

[21] Ingrid Skjong et al., How to Choose the Best Running Shoes for You, New York Times (Nov. 6, 2023), https://www.nytimes.com/wirecutter/reviews/best-running-shoes/ (emphasizing that all running shoes maintain the same skeleton, but vary within the drop, cushion level, and material. See Exhibit 3 for more detail); see also Dennis Green, Nike and Adidas are making huge investments that should terrify Under Armor, Insider (June 7, 2017), https://www.businessinsider.com/morgan-stanley-note-on-adidas-nike-2017-6#:~:text=Both%20Nike%20and%20Adidas%20have,in%20the%20last%20five%20years.%22 (exemplifying how much money companies spend on shoe development research); Tech innovation is our superpower; on (last viewed Nov. 8, 2023), https://www.on-running.com/en-us/explore/technology (using On as another example of how much time, energy, and money goes into developing running shoes).

[22] Amol Walgude, The Comfort Revolution: Shoes with Knitted Uppers Take Over, LinkedIn (Feb. 14, 2023) https://www.linkedin.com/pulse/comfort-revolution-shoes-knitted-uppers-take-over-amol-walgude/.

[23] 35 U.S.C. § 103.

[24] Adele Peters, The Race To Create Knitted Shoes That Cut The Wastefulness Of Our Footwear, Fast Company (Mar. 25, 2024), https://www.fastcompany.com/3027386/the-race-to-create-knitted-shoes-that-cut-the-wastefulness-of-our-footwear#:~:text=In%202012%2C%20both%20companies%20released,a%20similar%20shoe%20months%20later.

[25] Mary Hale, Enacting Sustainability in Footwear Product Development (2021)(Graduate dissertation, University of West Virginia)(on file with University of West Virginian library) (reporting that in 1996 Nike was first targeted for using child labor and manufacturing unsustainable shoes).

[26] See id.

[27] New Balance and Manufacturing in the US, New Balance (Sep. 16, 2020), https://support.newbalance.com/s/article/New-Balance-and-Manufacturing-in-the-US (using New Balance as one example to illustrate the number of shoes manufactured each year within the United States alone).

[28] Move to Zero, Nike (last viewed Nov. 8, 2023), https://www.nike.com/sustainability.