By: Sara Dalsheim

The NCAA is a billion dollar organization that manages the schools, conferences, and students who participate in college athletics.[1] The NCAA earns its revenue through television and marketing rights fees, tournament tickets, parking, concessions, merchandise, and a slew of other business ventures.[2] However, without the actual college student-athletes dedicating their time and efforts into their sports, the NCAA would be almost worthless.[3] Students sacrifice their time, which should be dedicated to enhancing their education in order to put forth their best effort for their respective team; and in most cases these athletes are dedicating more time to their teams than would normally be required in a full-time job.[4] Very few of these college athletes go on to professional organizations and the majority of their athletic careers end in college.[5] Consequently, college athletes invest all of this time into a billion dollar organization and system where they reap little to no benefit in return.[6]

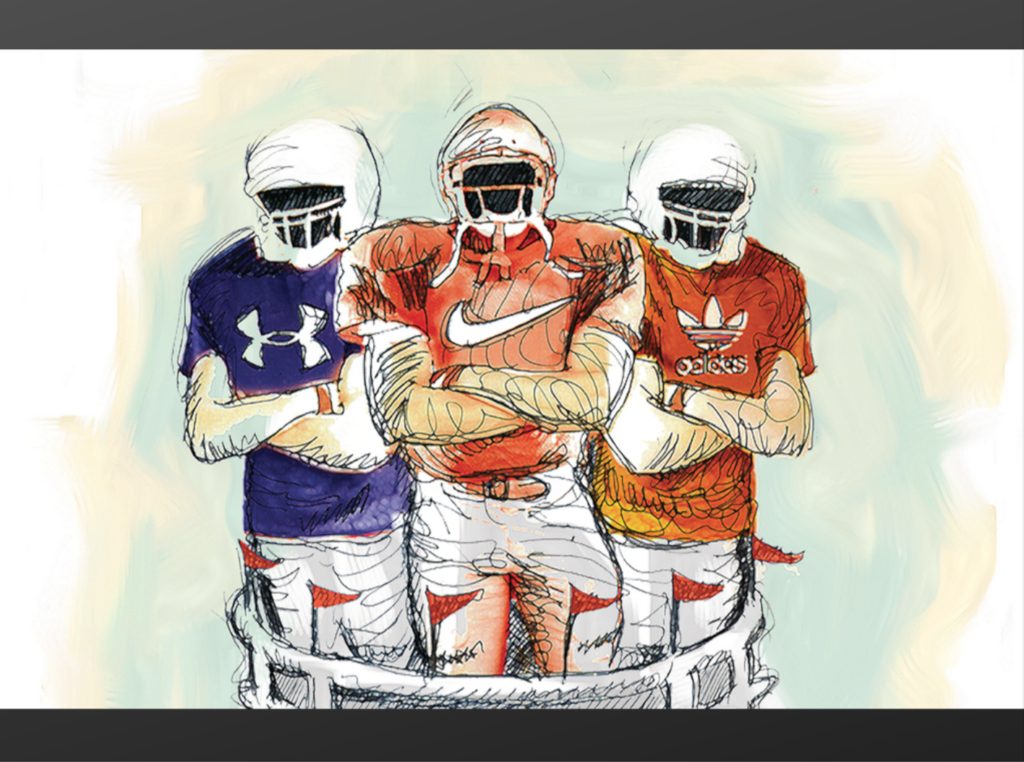

Most individuals believe that college athletes should be paid, but the issue still remains that traditional avenues are not viable because student-athletes are not employees under the law.[7] Under other proposed revenue-generating payment structures, critics have highlighted that they are not viable because award based payment structures may violate Title IX.[8] As a result of the immense revenue that the NCAA generates through male-dominated sports like football and basketball, any sort of system centered on how much value a team generates to a university would disproportionately compensate the male athletes and leave females with little to nothing.[9] So the best way to compensate college athletes is through endorsement deals for their own “likeness and image”.[10] The system would allow the athletes to be financially compensated without even costing the NCAA or the individual schools any money.[11] These athletes could capitalize on this short period in their lives where their likeness and images have a strong dollar value.[12]

Furthermore, endorsement deals would allow student-athletes to use their own athletic merit and generate income proportional to their athletic talent and appeal.[13] Sponsors would target the athletes that they believe deserve recognition and can resonate with their target market, regardless of their sex.[14] Endorsement deals would give college athletes an equal opportunity to either independently pursue these ventures or have sponsors pursue the athletes.[15] Those athletes who are the standouts and substantial contributors to the NCAA’s billion dollar revenues would be able to pursue their own profits, and their countless hours of athletic contributions would no longer be monetarily worthless.[16]

However, currently,

NCAA Bylaws forbid student-athletes from simultaneously engaging in endorsement

or paid media appearances.[17] These rules should be overturned;

student-athletes deserve compensation for their time and effort they contribute

to the billion dollar success of the NCAA.[18] The NCAA justifies these Bylaws by asserting

that they are protecting the athletes from getting taken advantage of; however,

the NCAA is likely attempting to make sure that all potential revenues stay

within the organization and not to the student-athletes.[19] If employment laws and Title IX will not

provide an avenue for compensation, then the NCAA should step up and gives its

athletes the economic opportunity they deserve.[20]

[1] Alex Kirshner, Here’s How the NCAA Generated a Billion Dollars in 2017, SBNation (Mar. 8, 2018, 7:00 AM), https://www.sbnation.com/2018/3/8/17092300/ncaa-revenues-financial-statement-2017.

[2] See id. (listing all of the NCAA’s income generating business ventures).

[3] Cf. id. (discussing the NCAA’s mass revenue while insinuating that it is all kept within the organization and not given to the those young individuals that truly generated it).

[4] See Greg Johnson & StudentNation, The NCAA Makes Billions and Student Athletes Get None of It, The Nation (Apr. 9, 2014), https://www.thenation.com/article/ncaa-makes-billions-and-student-athletes-get-none-it/ (“Despite devoting forty to sixty hours per week to their sport most of the year . . . players aren’t considered employees and lack basic economic rights under the NCAA’s cartel restrictions.”).

[5] See generally, NCAA Recruiting Facts, NCAA (updated Mar. 2018), https://www.ncaa.org/sites/default/files/Recruiting%20Fact%20Sheet%20WEB.pdf (stating that “fewer than 2% of NCAA student-athletes go on to be professional athletes”).

[6] Cf. id. (insinuating that student-athletes need to prepare for careers after college that do not involve athletics whatsoever).

[7] See Berger v. NCAA, 843 F.3d 285, 293–94 (7th Cir. 2016) (holding that as a matter of law college athletes are not employees who are entitled to minimum wage under the FLSA); Northwestern Univ. & Coll. Athletes Players Ass’n, 2015 NLRB LEXIS 613, *29-30 (N.L.R.B. Aug. 17, 2015) (refusing to assert jurisdiction over the private school college athletes and effectively refusing to let the college athletes unionize); Waldrep v. Texas Emp’r Ins. Assn., 21 S.W.3d 692, 697 (Tex. App. 2000) (ruling that receiving a scholarship or financial aid does not make an athlete become the university’s employee by agreeing in return to participate in university-sponsored programs, and therefore, the student is not entitled to workers’ compensation).

[8] See Jane McManus, Pressure to Pay Student-Athletes Carries Question of Title IX, ESPN (Apr. 19, 2016), https://www.espn.com/espnw/culture/feature/article/15201865/pressure-pay-student-athletes-carries-question-title-ix (“Title IX, which mandates equal access to school services regardless of gender, is often viewed as an inconvenience to the real goal of programs: maximizing revenue from men’s basketball and football.”).

[9] See Mechelle Voepel, Title IX a Pay-For-Play Roadblack, ESPN (July 15, 2011), https://www.espn.com/college-sports/story/_/id/6769337/title-ix-seen-substantial-roadblock-pay-play-college-athletics (“In regard to the concept of pay-for-play,’ Title IX is generally seen as a substantial roadblock. But not just because of the gulf between football/men’s basketball and women’s sports, but also because of the gap between those ‘big two’ sports’ profit-producing programs and virtually all other collegiate sports, both male and female.”).

[10] See Johnson, supra note 4 (arguing that student-athletes should be able to operate within the free market like any other employee, and therefore “be able to sign endorsements for their own likeness and image”).

[11] Gary Parrish, Everybody Wins if the NCAA Will Allow Players to Accept Endorsements, CBS Sports (Apr. 12, 2016, 9:28 AM), https://www.cbssports.com/college-basketball/news/everybody-wins-if-the-ncaa-will-allow-players-to-accept-endorsements/.

[12] Id.

[13] Johnson, supra note 4.

[14] Id.

[15] Michael Aiello, Compensating the Student-Athlete, 23 Sports L. J. 157, 166-67 (2016).

[16] See generally id. (arguing that allowing student-athletes to seek out endorsements would permit “the free market system to determine the value of the student-athlete.”).

[17] See NCAA Bylaw art. 12 § 1.5.1.3 (2018) (allowing students to receive money for something done prior to becoming a student-athlete, but it must be for something independent of athletic abilities); NCAA Bylaw art. 12 § 4.1.1 (2018) (proclaiming that student athletes cannot receive remuneration from an employer for the value or utility that the student-athlete may have because of publicity, reputation, fame, or personal following they obtained because of their athletic abilities); NCAA Bylaw art. 12 § 5.2.1 (2018) (stating that an individual will not be eligible for participation in intercollegiate athletics if he/she: “(a) accepts any remuneration for or permits use of his/her name or price to advertise, recommend or promote directly sale or use of commercial product or service of any kind, or (b) receives remuneration for endorsing commercial product/service through individual’s use of such product/service.”).

[18] See Johnson, supra note 4 (“There is no evidence to suggest that athletes being compensated a fairer market value would compromise an educational mission.”).

[19] Bloom v. NCAA, 93 P.3d 621, 626 (Colo. App. 2004) (using the NCAA’s “Principle of Amateurism” to protect athletes and clearly draw the line between amateur and professional athletics).

[20] See Aiello, supra note 13 at 167 (stating the NCAA should change its bylaws and allow student-athletes to enter into endorsement contracts, but in doing so should protect athletes by also allowing them to have agents).